Biology

How the World's Largest Salamander Feed?

An international team has developed three-dimensional models of the bite of the world's largest living amphibian, the Chinese giant salamander. The study, led by Josep Fortuny, researcher at the ICP and published in the journal PLoS ONE, explains the feeding mechanisms of this enigmatic endangered animal of which biology is poorly understood. Research reveals that this salamander feeds especially on preys located right in front of it but can also perform quick strikes on laterally approaching animals. Understanding how this species hunts not only broadens the knowledge of its biology but can also help in reconstructing how early tetrapods and extinct amphibians fed.

References

Fortuny, J.; Marcé-Nogué, J.; Heiss, E.; Sanchez, M.; Gil, L.; Galobart, À. 3D Bite Modeling and Feeding Mechanics of the Largest Living Amphibian, the Chinese Giant Salamander Andrias davidianus (Amphibia:Urodela). PLoS ONE. 2015, vol. 10, num. 4, e0121885. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121885.

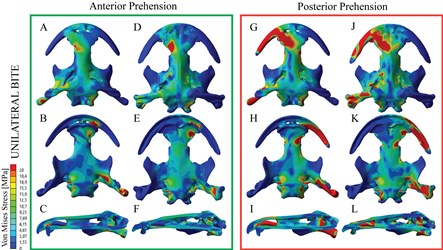

Researchers at the Institut Català de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafont (ICP) and the Laboratory for the Technological Innovation of Structures and Materials (LITEM) of the Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya (UPC) have modelled the biomechanics of the bite of the Chinese giant salamander from 3D CT-scan images of skulls of this species and applying a finite element analysis, a method for simulating complex physical and biological problems computationally. In this case, this method is particularly useful for investigating the distribution of forces within the skull of extinct animals or living animals using non-invasive techniques. Video with 3D bite modeling and feeding mechanics of the Chinese giant salamander is available online.

The giant salamander feeds on crustaceans and worms, but also on fish, amphibians and other small mammals performing a sit-and-wait strategy and biting when they are close enough. This salamander typically captures their prey by suction feeding, a common system in amphibians, but also capturing prey directly by the jaws. The position where prey contacts the snout is crucial and biting is especially optimal when the prey is directly in front of the animal. However, the study reveals that this salamander can also perform an asymmetric strike, that is biting only with one side of the mouth. This is a unique feature among vertebrates and allows them to capture laterally approaching prey. Once trapped, the salamander pulls the prey to the back of the jaw where a stronger bite is performed to prevent prey from escaping.

The coordinator of the Virtual Paleontology research group of the ICP, Josep Fortuny, heads the study. "The position where the prey comes into contact with the skull and jaw of the salamander shows us that there are some areas that are better than others when biting, being optimal when they bite with the anterior part on the snout. Possibly, when the prey is situated in a less optimal position the animal has to bite twice: one to catch the prey and again to put in a frontal position", explains Fortuny. This is possibly related to the architecture of the skull of these animals, they lack of a bony bridge between the posterior end of the maxilla and the anterior quadrato-squamosal region, typical of most salamanders.

Figure 1: Distribution of forces in the jaw in a unilateral bite. Photo: ICP/LITEM.

Paleontologists are interested in the bite of this living animal because the Chinese giant salamander belongs to the oldest known group of amphibians, the Cryptobranchids, which appear 161 million years ago, during the Jurassic period. This is what is often miscalled a "living fossil", an animal that has changed relatively little from their ancestors throughout evolution. In fact, the first amphibians were aquatic predators, with a long flat skull, similar to this species, so the characterization of its bite can help to understand how their ancestors fed.

LITEM has performed the most technical part of the study, transforming tomographic images in a CAD model and developing a finite element model that shows how muscle forces are distributed. “We have applied methods from the field of mechanical engineering usually used to study and calculate the behaviour of structures such as buildings, chassis cars, planes, etc. and applied to vertebrates, which basically differ by having a more complex geometry and are made of bone, instead of steel or concrete. So we recreate the mechanical behaviour of salamander skull when biting and infer biological issues from it”, says Jordi Marcé-Nogué, the UPC researcher who participated in the study.

Figure 2: Researcher Egon Heiss with a live specimen. Photo: Egon Heiss.

An endangered giant

The Chinese giant salamander is the largest living species of amphibian, reaching a maximum length of 1.8 metres. It lives in cool, fast-flowing streams and mountain lakes. Their large size, lack of gills and inefficient lungs confine this species to flowing water as the main oxygen uptake is through the skin. Individuals are dark brown, black or greenish in colour with irregularly spotted patterning. It is generally nocturnal, is generally nocturnal, although they become more diurnal during the breeding season.

The species is included in the Red List of the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) and in critical danger of extinction due to indiscriminate hunting for human consumption and degradation of their natural habitat.

Top left figure: The Chinese giant salamander (Andrias davidianus) is the largest amphibian in the world. Photo: Egon Heiss.

Institut Català de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafont (ICP)

2025 Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona

B.11870-2012 ISSN: 2014-6388